Quincy Jones, the celebrated polymath of American music, has passed away. The outpouring of admiration for this much-loved artist spoke volumes for his vast imprint on popular music across a swathe of genres. His unfailing taste and judgment enriched the careers of artists in jazz, pop, soul, and R&B, and across films and television. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee was also a recipient of the Grammy Legend Award, the National Medal of Arts, the John F. Kennedy Center Honors, and other accolades without number.

Jones worked with many of the undisputed greats, from Ray Charles to Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington to Sarah Vaughan, and Frank Sinatra to Michael Jackson, and changed the careers of countless others, such as Lesley Gore, the Brothers Johnson, Donna Summer, George Benson, and James Ingram, to name only a few. Even if he had done nothing else, “Q” was the producer of what remains the bestselling album in recording history, Jackson’s Thriller, not to mention his Off The Wall before it and Bad afterwards.

Early life

The exceptional life of Quincy Delight Jones Jr. began on March 14, 1933, when he was born in Chicago. His parents split up when he was young, and at ten, he moved with the family, including his step-mother Elvera, to Bremerton, Washington. His birth mother Sarah, for all her personal problems, had already made sure that the music bug bit him hard, and in high school he began to show his jazz chops, as both trumpeter and arranger. In 2018, in the podcast series What It Takes, Jones remembered how music set him on the straight and narrow. “One night we went and broke in another door,” he said, “…and there was a piano there. And I just walked around the room to see what was there first, and then [my] hands kind of hit the keyboard.

“And I remembered from Chicago, next door when I was a kid, there was a little girl named Lucy that used to play piano. And from that moment on, when I touched those keys, I said, ‘This is it. I’m not going to do the other thing again. I’m going here.’ That’s what happened.”

When Quincy was 14, he introduced himself to a 16-year-old Ray Charles, whose precocious talent and achievements against the odds became a recurring inspiration. Jones won a scholarship to Seattle University, where his fellow students included Clint Eastwood, and studied at what became Berklee. He received a Honorary Doctorate of Music from the college in 1983.

Jazz beginnings

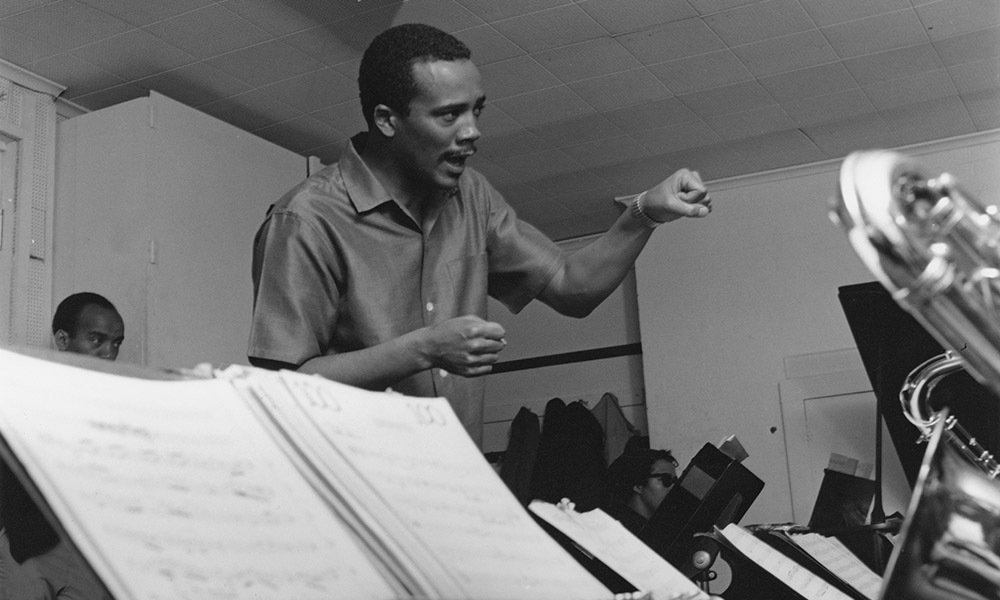

Soon, his multifarious talents were in demand, and he went on the road with Lionel Hampton’s band before moving to New York, where he wrote freelance arrangements for such greats as Ellington, Basie, Sarah Vaughan, and Dinah Washington. His experiences were anything but limited to the US: he toured Europe with Hampton in 1953 and later the Middle East as musical director, still in his early 20s, for Dizzy Gillespie.

In 1955, EmArcy released Jazz Abroad, on which he shared the billing with jazz drummer Roy Haynes, on live recordings made over the previous two years in Sweden. Then his name was above the title for the remarkable ABC-Paramount album This Is How I Feel About Jazz. Produced by Creed Taylor, it amply displayed his virtuosity in a variety of band settings, from a nonet to a 15-piece big band, and featured such greats as Art Farmer, Phil Woods, Milt Jackson, Art Pepper, Zoot Sims, and Herbie Mann.

“Quincy Jones is one of the best things that has happened in jazz in many years,” raved Billboard in its review. “A young arranger-composer who can write modern, but with an understanding of the basic, timeless spirit of the idiom.”

A second LP for the label, Go West, Young Man!, was followed by the Metronome release Quincy’s Home Again, in 1958. That year, at 25, he met Sinatra, for whom he arranged some of the vocalist’s best later records, as they became lifetime friends. But prestige was not proving equal to financial gain, and Jones struggled to make ends meet.

A job at Mercury Records would provide not only greater stability, but the grounding in the business of music that would set him apart from less inquisitive musicians. Deftly combining business and creative roles, he began a long recording association with Mercury on 1959’s The Birth of a Band!, which merited a ranking in Billboard’s jazz charts.

By 1961, he was label VP, breaking new ground for an African-American executive. Several albums later, Jones first made the all-genre album listings on the last chart of 1962, with the Mercury release Big Band Bossa Nova. It included the future staple, and to this day one of those tunes that everyone knows without necessarily being able to name it, the irresistible “Soul Bossa Nova.”

In 1963, Jones told Melody Maker of his arranging technique: “When you’re planning a record, the first thing you have to find a direction, make a programme or decide on a mood, or a variety of moods. You must have a reason to take the session some place. How do you decide? Well, you consider the artist’s catalogue and repertoire, what he’s made in the past. After that, it’s mostly intuitive.”

Pop producer

Displaying the ear for pop talent that would be another part of his armory, he achieved his first hit single as a producer in that year of ’63, with one of the quintessential pop 45s of its day. New York discovery Lesley Gore was not yet 16 when Jones sat at the desk on “It’s My Party” and watched it go all the way to No.1 on the Hot 100. Three further smash hits, all produced by Jones, followed for Gore in “Judy’s Turn to Cry,” “She’s a Fool,” and “You Don’t Own Me.”

In 1964, Jones’ career became even more multi-media, to use a latter-day term, when he composed the first of some 40 film scores, for Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker. Its success prompted his relocation to Los Angeles, where subsequent soundtracks included many enduring, heavyweight pictures including In the Heat of the Night, The Italian Job, Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, The Out-Of-Towners, They Call Me Mister Tibbs!, and The Color Purple.

On the small screen, he turned his hand to well-remembered themes for such forever-syndicated shows as Sanford and Son; Ironside, starring Raymond Burr; and the first episode of the epic series Roots. In 1971, he directed and conducted the music for the Academy Awards ceremony, another first for an African-American.

As a recording artist, he won Grammy Awards for 1969’s Walking In Space and 1971’s Smackwater Jack, and went gold in the US with 1974’s Body Heat and the 1977 Roots soundtrack. But even greater acclaim was just around the corner. 1978’s Sounds…And Stuff Like That! was a platinum-seller in America and international success, fuelled by the hit single “Stuff Like That” featuring Chaka Khan.

That LP established a template that Jones would use again, of employing A-list vocalists and instrumentalists for guest spots. It was a recipe that took 1981’s The Dude into countless homes, with its sequence of hit singles including “Ai No Corrida” and two that brought James Ingram to the wider public with his soulful delivery, “Just Once” and “One Hundred Ways.” Patti Austin was an equally inspired choice as the other featured singer, memorably on “Betcha’ Wouldn’t Hurt Me” and “Razzmatazz,” the latter written by Englishman Rod Temperton.

Jones’ bond with the latter songwriter-arranger was already a fixture. In 1979, Quincy partnered with Michael Jackson, who was 12 when they first met, and played the major part in his emergence as a true global icon. The first installment was Off The Wall, featuring a title track and two others written by Temperton; in February 2021, the album was certified nine-times platinum in the US, from an estimated global total of 20m.

But even that paled by comparison to Jones’ next collaboration with Jackson, the indelible Thriller, which was released in November 1982 and proceeded to shred every sales record known to the industry. It remains the biggest-selling album in history, with seven major hits and eight Grammys to its name among endless other achievements. Jones and Jackson’s third and final studio pairing came with another landmark blockbuster, 1987’s Bad.

By then, the producer had further burnished his already-unrivaled credentials as the man who demanded that a roomful of superstars should “leave their egos at the door” for the creation of the ultimate charity fundraiser single, 1985’s “We Are The World.” It starred Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles, Tina Turner, Billy Joel, and countless others, won three Grammys, and became another 20 million-seller. The who’s-who cast list essentially equated to Jones’ unrivaled contacts book.

It was typical of his mastery that when he resumed his output under his own name, the record in question won another Grammy, for Album of the Year. Back On The Block was an era-uniting stroll through Quincy’s past and present, featuring stars of the day such as George Benson, Luther Vandross, Al B. Sure!, and another new discovery, 12-year-old Tevin Campbell, but also all-time giants like Ella Fitzgerald, Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughan, and Dizzy Gillespie. It’s hard to think of any other producer who could have called on such a cast.

“It’s disgraceful to have young kids who don’t know who Duke Ellington is,” Jones told The Guardian in 1990. “The whole history of black people in America is documented in music and yet with so many young inner city kids there’s no sense of connection to anything. But it’s no accident that everyone in the world is keyed into black music because nobody was ever forced to go into the soul as deep as where slavery pushed everybody. There was no refuge, no place to go but down, inside.”

In 1995, Q’s Jook Joint was another platinum-seller and Grammy winner, this time for its engineering. It boasted such guests as Bono, Stevie Wonder, and Ray Charles (together on “Let The Good Times Roll”), Barry White, Gloria Estefan, and Ronald Isley. 2010’s Q Soul Bossa Nostra revived songs close to Jones throughout his career.

Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones was published in 2001. He continued to pursue new musical and business endeavors with almost impossible energy until late in life, and in 2017 he founded Qwest TV, a subscription service for jazz and international music, with French producer Reza Ackbaraly. “I feel like I’m just starting,” he told GQ in 2018. “I never been this busy in my life.”